JLG

On the mad master of the French New Wave

Jean-Luc Godard is dead. He was, without a doubt, the last great European filmmaker of the twentieth century. Today, no living filmmaker has as much impact on the medium as Godard did. None has as varied a filmography. It is hard to convey to non-filmmakers just how invigorating watching a Godard film can be for someone who makes films. One Godard film contains more cinematic ideas than other directors’ entire filmographies. A partial, improvised list of examples might include: jump cuts, hypnotic titles, olympian tracking shots, direct address to the camera, Brechtian staging, conceptual stunt casting, found footage essays, frames within frames, novelistic narration, the whispered voiceover, characters reading from books, dialogue made up entirely of quotations… and all this can be found in a single film.

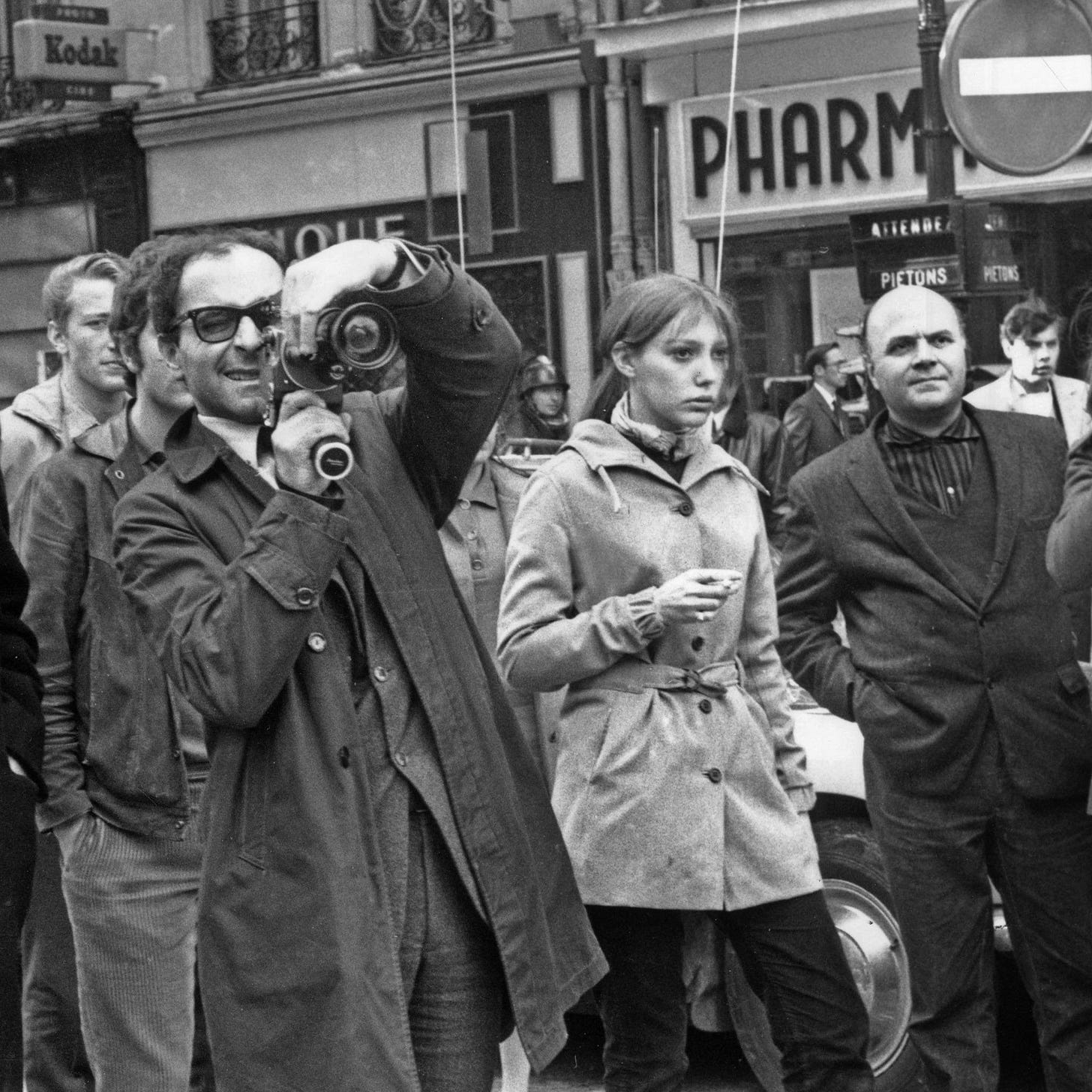

In distinction to the protean filmmaking, the man himself was eternally recognizable: the glasses, the cigar, the blazer, the bon mots. He was too often reduced to a generator of highbrow soundbites, repeated ad nauseum: Make films politically, truth at 24 frames a second, a girl and a gun, etc. Most people never knew the quotes’ contexts, almost none read his early criticism, and fewer still watched more than Breathless (1960) and Contempt (1963). Part of this was his own doing: in later life he courted obscurity, turning his back on mainstream success to become a filmmaker’s filmmaker. I know very few Godard obsessives who aren’t involved in the arts in some way, and a lot of those people are filmmakers themselves. He had decimated his audience with his formal radicalism, opting, as he put it somewhere, to make films for about thirty-thousand friends.

Even among those happy few, there was a deep fragmentation in his reception: radical types who knew nothing about classic Hollywood, film geeks who never read Arendt, and fashionistas who just salivated over the cool clothes and pretty actors. Stills from La Chinoise (1967) are often included in artworld and fashion articles mostly because—admit it—the film looks great, not because anyone in the West has any sympathy for Maoism anymore. Then again, Godard probably didn’t read much Mao, either.

By the start of the seventies, when Godard was in his early forties, his politics had matured—fairly late, by any standard. During much of the sixties, he was a kind of aesthetic anarchist. Cinema was his history, Langlois was his leader, the New Wave were his comrades. In the late sixties he cribbed (almost literally) his leftism from his new teenage girlfriend, the actress and student, Anne Wiazemsky. Pseudo-Maoism followed, and then began a period of intense political filmmaking alongside Jean-Pierre Gorin as part of the Dziga Vertov Group. The group broke up, Godard got into a near-fatal motorcycle accident, and he moved to Switzerland. For the rest of his life, his politics would be on the left, more or less as they had been in the early seventies.

Those politics are far weirder than polite company would admit. He could be his own worst enemy, especially when his ego was involved—which it always was. Put less charitably: his chauvinism sometimes got the better of him. He was a feminist whose films could also be embarrassingly sexist. (See Jane Fonda’s treatment in Letter to Jane, 1972, and the multiple debasements of Every Man for Himself, 1980.) He was probably the most sensitive critic of the conditions of Hollywood filmmaking, but he regularly humiliated people on camera to make his point. (The children of France/tour/détour/deux/enfants, 1977, for example.) Behind the camera he was no better. He preached making films politically, but he wasn’t the best boss. And, to paraphrase Truffaut, he could he be a shit to his fellow directors. Most damningly, his casual antisemitism, well documented in Richard Brody’s biography, regularly undermined whatever good he had to say about Palestine or the Holocaust.

But unlike a lot of the May ’68 generation, he never sold out—an ethical position that is distressingly scarce today. He directed few commercials, I’m unaware of any music videos, and his flirtations with Hollywood went unrequited. He probably could have been generously compensated if he had just crawled back to Paris in the 1970s and made a straight-ahead romantic drama. He never did.

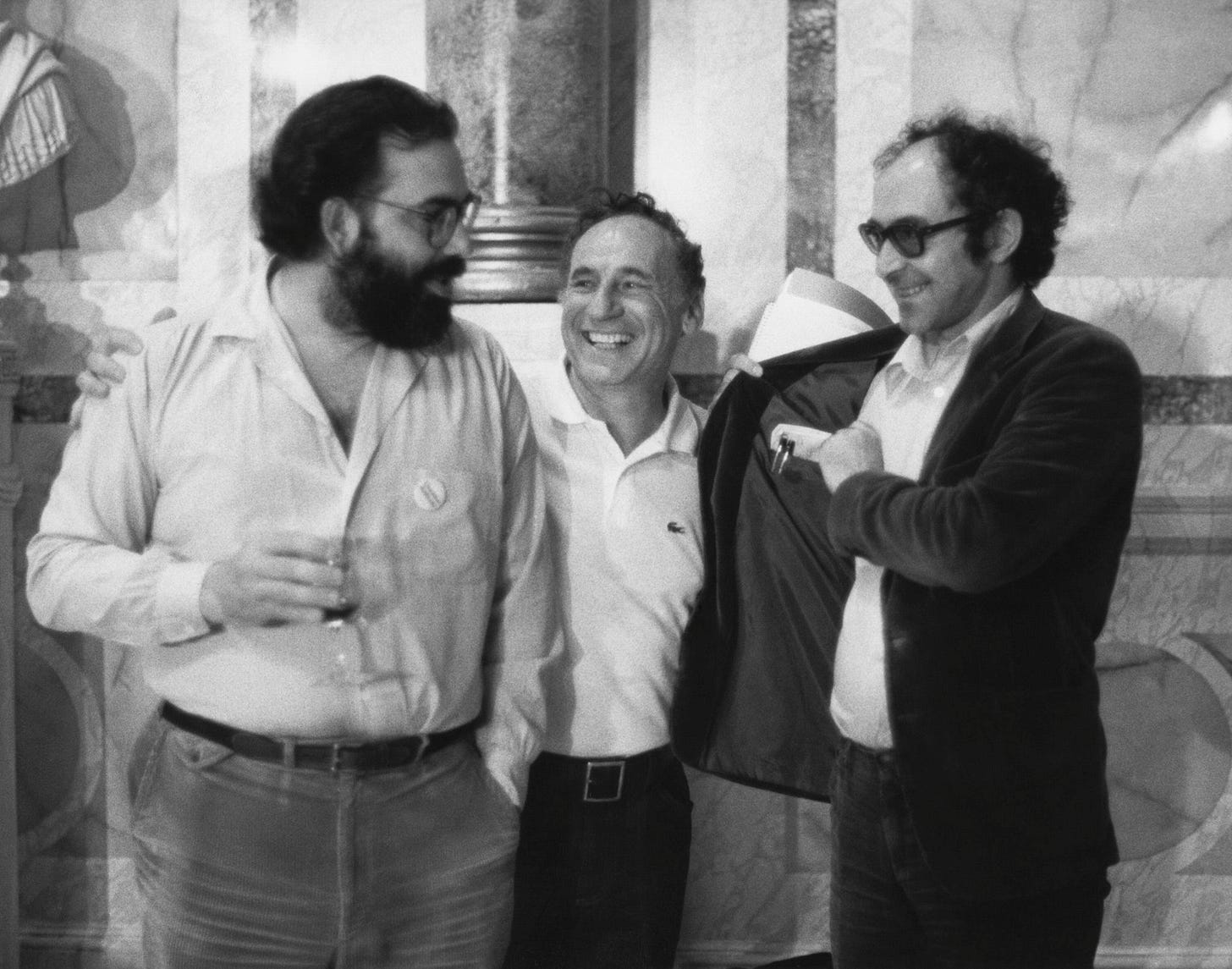

For better and worse, Godard was disinterested in fulfilling the financial obligations that come with producing mass culture. The subsequent exile from “the industry” was lifelong: After the 1960s, Godard struggled to put together even the tiniest of budgets, despite being one of the most famous filmmakers in the world. (I forgot where I read this, but during a visit to Hollywood, he supposedly said to fans he met, “If you admire my films so much, why don’t you give me twenty bucks?” Mel Brooks was the only person who opened his wallet.)

When it came to feminism and treating colleagues well, his politics were often self-defeating, but there are few other European filmmakers of his generation who gave as much screen time to anticolonial struggle. Texts of Black revolutionaries like Stokely Carmichael and Frantz Fanon are woven into Weekend (1967). Omar Diop, a little-known Senegalese student radical, appears in two of Godard’s films. (The American-Belgian filmmaker, Vincent Meessen, has made an excellent documentary about Diop.) Godard’s work building postcolonial Mozambique’s TV industry was singular for its utopianism and criticality, though the project eventually failed. His commitment to the Palestinians was continuous throughout his later career—in fact, it formed backbone of much of his political worldview. Ici et ailleurs (1976) remains one of the important European films made about the Palestinian struggle, and—yes—the difficulties of making films politically.

Godard’s politics were always refracted back through images. Images, images, images… no narrative, no idea, no political formation, no relationship could stand on its own for Godard without the image. He understood the entire production and distribution of images from the studio to the theater to the living room and back. Printed books, paintings, silent films, commercials, political propaganda… as he said, everything is cinema, and one could also say, everything is images.

To control images was to control politics, and being a director put one at the switchboard of political power. At the same time, Godard was aware that you just couldn’t hand workers a microphone and camera and expect them to make liberatory cinema. (They would probably remake what they watched on television anyway.) Hollywood and television had already foreclosed most political speech, especially for those who most needed an alternative political vision. Spectacle had rendered audiences politically insensate.

This is heady stuff, especially for those dissatisfied with conventional narrative cinema and documentary. Godard was carrying out a two-front critique: It wasn’t just enough to dramatize politics or interview the workers leaving the factory. One had to think about the process of filmmaking politically and show that process in the film itself. For a while, it seemed like every Godard interview, new film, short video, contained some little revelation on how to make a new political cinema. It really did appear that he knew something no other filmmaker did.

Which also meant that he could be a terrible influence on young filmmakers in search of a guru. He made it look easy, giving neophytes the false impression that formal innovations were shortcuts to good politics. He created cul-de-sacs for young artists, which meant that Godard, ultimately, was a phase to outgrow, or to grow through. To be honest, before his death I hadn’t thought about his films in years—which is saying something, considering that I used to think about and watch his films every day. That’s not an exaggeration, either. His films had a way of trapping filmmakers in their worldview.

The result is years-worth of sub-Godardian artists’ films clogging the ether, experimental cinétracts of chopped-up musical cues and endless dolly shots, all voiced-over with whispered Heidegger quotes. Even mainstream narrative filmmakers like Brian De Palma fell under his spell, at least during the late sixties when Godard was a global sensation. One of the other better-known examples is Bernardo Bertolucci’s Partner (1968), an awkward Godardian misstep released just two years before his masterpiece, The Conformist (1970). Godarditis can strike even the best of us.

Part of this was due to the scale of the intellectual territory under consideration. Godard’s filmography is a university-sized aesthetic curriculum, complete with a filmographic canon (Ford, Lang, Ray…) a political program (Marx, Arendt, Fanon…), literary reading lists, stars to admire, even clothes to wear and music to listen to. Unsurprisingly, there was (maybe still is) a class at Harvard that spent the entire semester only analyzing and tracking the references in Vivre sa vie (1962).

As much as Bowie or Dylan, there was a Godard for everyone: the young Turk, ready to overturn the film industry; the starlet-dating jetsetter who wore sunglasses to the movies; the proto-punk radical shouting epithets at Cannes; the Hollywood-bound European with a chip on his shoulder; the commie-curious fellow traveler, ready to mix Marx and Coca-Cola. It all settled into the late Godard: Godard the aesthete, retired to his Swiss home studio with his Goethe and his Mozart. It was this Godard that was the most difficult to understand, the hardest to cheer, and the least written about, at least in English. (Brody’s biography is the one great exception.)

It is also the Godard I like best. Not quite post-cinema, definitely not post-political, the grumpy old man puttering about the house, reading Hölderlin, musing on the Palestinians or the war in Bosnia, watching laserdiscs of Renoir films while chain-smoking Havanas. The films from this period have an unearthly beauty, as if they were made for some future alien audience that only Godard could communicate with. He seemed very alone late in his life, although he lived and worked alongside the largely unsung Anne-Marie Miéville. It wasn’t the worst way to live, though he didn’t appear exactly happy either. He was something far better: an artist who had become indistinguishable from his medium.