The End Is Never the End, Part Two

On haunted house films

Note: This is the second part of a two-part essay. The first part can be found here. A shorter version of this essay was originally published in the journal Nova Express. All stills are from my related film Haunting (2020).

Staircase

It’s there in every film—winding, enormous, central to the house, central to the story. The symbolism is obvious: up to the afterlife, down to the lower depths. It divides the house into psychoanalytic categories, too, with the superego in the attic, the id in the basement, the ego caught in between. The Bates Motel might have been the first, or at least the most imitated. Characters must descend and ascend between the house’s levels at crucial moments in the film, preferably slowly and at night with a flashlight.

Under the staircase there is usually another staircase, sometimes hidden. This is the staircase to the basement, perhaps the most horrifying level of the house. Basements are so crucial for the genre that they even appear in geographies that don’t support them. This is true of the basement in Lucio Fulci’s The Beyond (1981), a film set in rural Louisiana where basements are non-existent. (To be fair, the film’s basement does suffer from predictable flooding problems.)

And just as there is a staircase under the staircase, there must be a basement under the basement, perhaps hidden behind a wall or a half-sized secret door. With this second sub-basement, we enter the dream logic of the haunted house film. This room contains the film’s secret, the character’s guilt, the house’s history. This is the room that no one should enter, but everyone will.

Chandelier

The staircase also provides the elevation necessary for a shot that appears in every film. It first occurs when the family enters the house at the beginning of the film. The camera is usually placed on the second story looking down, framing the chandelier, vestibule, and family below. (In some variations, the chandelier turns on just at this moment.) The shot appears in dozens of movies, almost at the same second, sometimes repeated several times in the same film.

This shot is so ubiquitous it even appears in Ju-on: The Curse (2000) during a scene set in a modest contemporary residence in Tokyo. In the film’s opening scene, when a young social worker forces her way into an elderly woman’s small home, the director frames the scene from the second floor, restaging the shot we recognize from films set in typically larger, Western houses. There is even a tiny low-cost chandelier off to one side, swaying for no known reason.

In these films, given enough time, the chandelier will turn deadly. It will crash to the ground sometime during the third act, threatening to crush the protagonist or some less fortunate character. One such chandelier—comically enormous—nearly kills George C. Scott’s character in The Changeling. Other chandeliers fall in House of Usher (1960), The Haunting (1963), The Legend of Hell House (1973), as well as in countless other films. In this way, the chandelier becomes a weapon for the supernatural (one of many), while providing a narrative device for the screenwriters. If there was any doubt before, the house is no longer to be trusted. To stay in the house is to ignore reality, a reality that itself is beginning to collapse.

Law

When things do unravel, no one, of course, calls the police. Either the idea is never brought up, or when it is, it is instantly dismissed. “They can’t help us,” is the usual explanation, and it’s true: the police can’t stop the supernatural. Maybe, for a moment, the mostly white protagonists of these films know what it’s like to not be able to call the cops. The lack of policing in horror films is usually used to dismiss the genre as unrealistic, as if calling the cops on an ancient demon would solve the problem. As everyone must know but pretends to forget, the absence of the law is the genre’s necessary precondition. As with psychiatry, the law exists only to be dismissed. When the police do appear, they are usually instantly killed or demoted to a supporting role. But, more usually, the police never arrive, because what we are witnessing is beyond any known law.

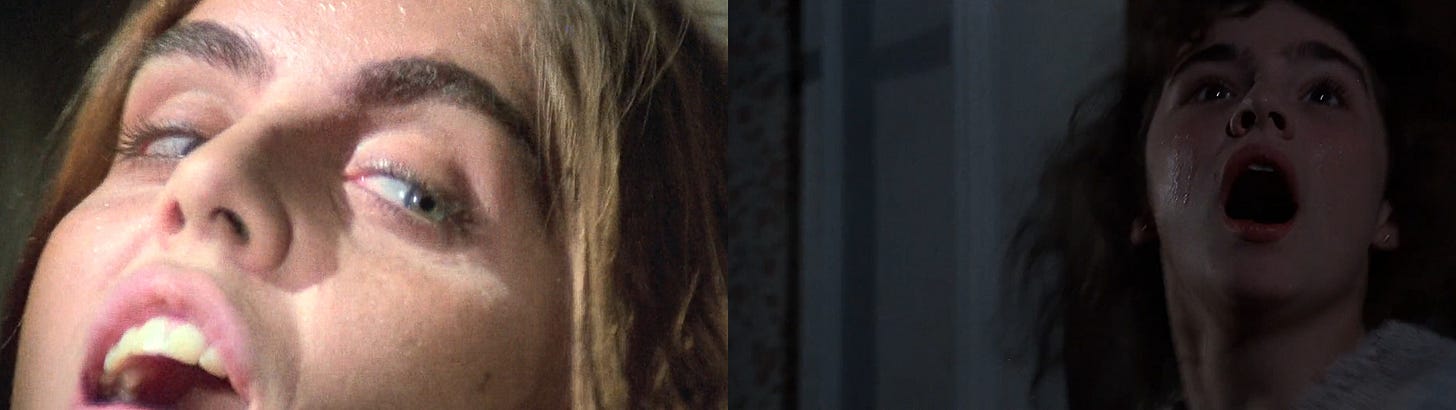

Scream

The actors in these films can’t always act, but they can always scream. The scream, like in pornography, is the signal to the audience that the necessary emotion is taking place. The emotion in pornography is pleasure. In horror, it is fear. (Or is it the other way around?) A scream is both sound and image, a high-pitched vocalization and a face contorted in a way that, if taken out of context, could also be a laugh. Hands placed in front of the wide-open mouth, the shake of the shoulders before the cry begins, the eyes wide and staring. In cinema, the scream is always stylized, the thousand wailing children of Marion Crane. No one screams so perfectly in real life.

In Brian DePalma’s Blow Out (1981) the protagonist, a film sound recordist played by John Travolta, searches for the perfect scream for a horror film. The film begins with the wrong scream—a flat whine, comical in its inappropriateness—and ends with a perfect Hollywood scream, which, in the film’s narrative is a “real” scream. But the first scream was closer to a real-life scream: pathetic, off-key, almost whimpering, maybe with eyes wrinkled shut.

Escape

And, of course, no one leaves. Just like the dinner guests in Luis Buñuel’s The Exterminating Angel (1962), the characters in a haunted house film are unable to flee their own terrifying predicament. The suggestion of flight is enough to reduce the whole genre to rubble. Again, realism is not the point, though the horror film’s antirealism is not identical to surrealism’s antilogic. As much as fear, fascination and curiosity drive the haunted house story, as do stubbornness and disbelief. The children in Poltergeist (1982) are sent away only after their sister has already been consumed by a television and one of them was attacked by a tree. (The parents stay on.) “This is my house!” screams the thickheaded father in The Amityville Horror (1979), as if his property rights were what was really at stake. Sometimes the excuse for staying is geographic isolation: such as with the snowbound Overlook in The Shining (1980). But The Shining holds the key to understanding this inability to leave: Jack is the ghost, and ghosts can never leave.

Undead

It is a common move in the haunted house film: the main character, who may or may not be alive at the beginning of the film, is eventually revealed to be a ghost. To take only one example: Alejandro Amenábar’s The Others (2001), which offers a scenario that perfectly enacts the idea. In the film, a mother (Nicole Kidman) and her two children live alone in mansion that they believe to be haunted. They never leave the house and seem unable to do so. By the end of the film, one learns during a séance that the mother and children are dead. They are the ghosts, and the entities we thought were apparitions are the current, living inhabitants of the house. Since the film is focalized around the mother and children—one only sees what they see—we have been led to falsely believe that the dead are the living and the living are the dead.

This should seem familiar. To borrow Andre Bazin’s term, all cinema is a mummification. All cinema keeps the dead in a state of suspension. Most films are populated by actors who have been dead for decades. Like the mother and children in The Others, their characters are forever repeating the same events, reenacting the same tragedies and false revelations, all the while unable to leave their boxes.

Fire

The first time was when it sank into the lake, illuminated by moonlight. A stone mansion, a structure of immense size disappearing downward. The villagers were there with their torches, but none of them had the chance to ignite the infernal thing. Years later, it burst into flames, a stone edifice now somehow combustible, the hero escaping at the last minute, dodging falling walls. The next time was in a small college town, and the building, this time, was a mansion with rooms to rent. It, too, burned down, but not before the music professor living upstairs caught a glimpse of his long-dead child standing in the flames. From then on, fire, always fire: a ballet school in New York City, an orphanage somewhere upstate. During the next decade, suburban families saw their one-family homes burning in their car’s rearview mirror. The local news reported a gas leak, or maybe a case of arson, but the surviving family knows the true reason. Then, once, the house actually collapsed inward on itself, imploding, as if sucked into its center by an enormous, subterranean vacuum cleaner. When the neighbors opened their eyes, the house had vanished, house consuming house, walls submerging into ground, familial interiority becoming its own devourer.

Epilogue

What comes after the end? What follows when everyone has returned to their families, their homes, their graves? What is the afterlife of the afterlife? For Barbara Creed, the horror film’s resting places are eternal. The story ends because abject monsters are vanquished, order restored. She writes: “The horror film brings about a confrontation with the abject… in order, finally, to eject the abject and redraw the boundaries between the human and the nonhuman.” Ejection, redrawing, finally. But is this what happens? Does the end ever take place in these films, finally?

Watching horror films—ghost films, but horror films in general—I am struck by how they often refuse to end, of how often the ending is supplanted by a second ending, a third ending, a chain of sequels. Whereas the epilogue usually shows the protagonist living happily ever after, the epilogue in the horror film shows that the horror is a lack of finality.

In the concluding scene of The Entity, Carla returns to her house, now emptied of furniture, only to be threatened again by the same ghostly sounds of which she believed herself to be free. She opens the door looking out to her front lawn, but instead of a terrifying ghost, she sees her family packing the remainder of their belongings in their car. A concluding title tells us that the “real Carla Moran is today living in Texas with her children,” and that “the attacks, though decreasing in both frequency and intensity… continue.” This narrative vacillation—the ghosts were exorcized, but they may still trouble the home, but she is leaving the home for good, but the attacks continue elsewhere—is, in fact, the norm for the haunted house film. And what else would we expect? Specters are themselves the violation of finality. For the specter, the end is never the end.