The Premises exhibition, Camel Collective, and Adorno's infamous phone call

Hello Everyone,

This week’s newsletter stitches together two texts: one short and one long; one published in 2019, the other published this month.

The shorter piece was my contribution to Museum Memories, a pamphlet edited by Claire Barliant and Katarina Burin. Museum Memories was published in 2019 as part of Katarina’s exhibition at Anthony Greaney Gallery, but went unlaunched due to the pandemic. It recently resurfaced at the Boston Art Fair, so I thought I’d include my contribution here.

In the introduction, Claire writes: “The motivation for this publication was simple: Since many museums—witness to much we can no longer recollect ourselves—are no longer around, we set out to capture memories of these museums, before they are lost for good.” A.S. Hamrah, Jenny Perlin, Shelly Silver, Byron Kim, Stephen Prina, and several others responded with short texts. I wrote about the defunct Soho Guggenheim (1992-2001) and an exhibition that itself was about notional architecture, Premises (1998-1999).

The second piece was published last month as part of issue 23 of OSMOS magazine. OSMOS is an organization made up of two New York arts spaces (Manhattan, Catskills) and a publication, all run by Cay Sophie Rabinowitz and her partner, Christian Rattemeyer. I wrote about the artist duo Camel Collective (Anthony Graves and Carla Herrera-Prats), whose work I’ve been following since their beginning. I’m happy to have finally been able to write about one of their films and go on about the Frankfurt School’s most infamous phone call.

I highly recommend tracking down and purchasing physical copies of both publications. They are handsome productions and contain contributions more impressive than my own. OSMOS is distributed by DAP (subscriptions here) and Claire tells me the Amant Foundation bookstore in Brooklyn is carrying Museum Memories.

For technical reasons, both texts are published here in their pre-edited forms, which, other than some egregious typos, don’t differ much from what made it into print.

Thanks for subscribing.

J

Museum Memories: The Guggenheim Museum SoHo

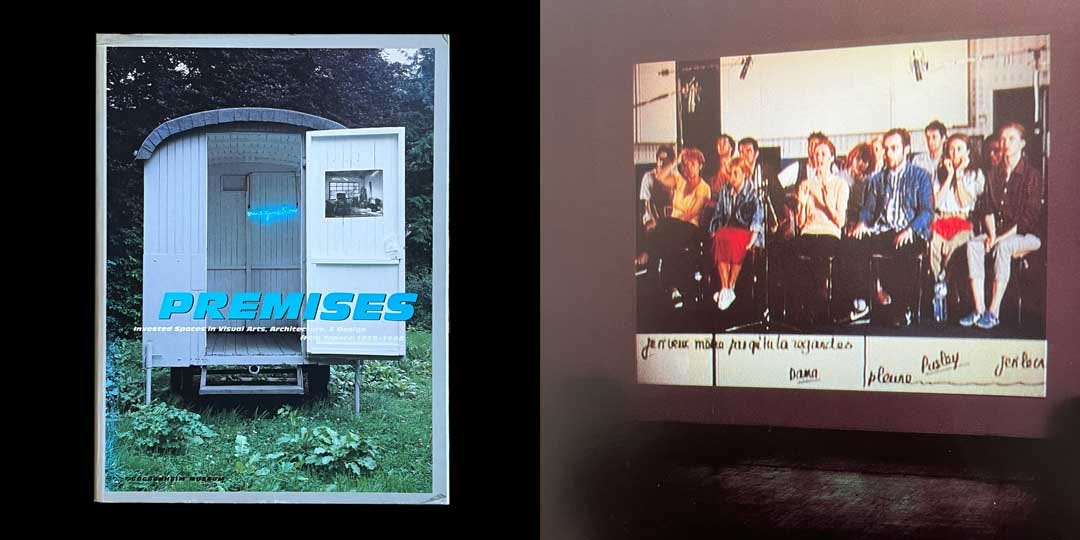

Plenty has been lost and very little gained in the twenty-five years since I arrived in New York. If I had to remember one space that is no longer with us, however reluctantly, it would be the Guggenheim Museum SoHo. In my four years as a student during the 1990s, the Guggenheim’s SoHo branch was a bland placeholder in downtown’s terminal culture. But, in 1998, the museum hosted Premises, an exhibition whose effect on me is still ongoing. Subtitled “Invested Spaces in Visual Arts, Architecture, & Design from France, 1958–1998,” the exhibition was, of course, organized by, if not bought readymade from, the Centre Pompidou. (Premises was curated by Bernard Blistène, Alison M. Gingeras, and Alain Guiheux.) Fittingly for this remembrance, the exhibition was devoted to virtuality of the francophone variety, with snapshots of Yves Klein leaping into the void (from multiple angles), unbuilt utopian superblocks of all kinds, Deleuze’s television Abecedarium, Delphine Seyrig sprawling across Last Year in Marienbad, plus my first glimpses of the work of Pierre Huyghe and Thomas Hirschhorn. (The latter, if I remember correctly, spent some time in the Prince Street windows making a typically deranged tin foil sculpture.) Every important element of my work in the last two decades owes something to that exhibition, and over the years I’ve bought and lost the catalog three times. (The most recent purchase was an online edition labeled “collectable,” a true sign of obsolescence.) The show closed sometime in ’99, and the museum closed soon after that. Today the space is Rem Koolhaas’s Prince Street Prada. One day soon, it too will be virtualized.

Camel Collective

Adorno called the cops. Anyone with a passing awareness of the Frankfurt School has heard this embarrassing fact, though the phone call’s context has become the stuff of tenured specialists. It was January 1969, and members of the Socialist Student Alliance (SDS)[1] had occupied Frankfurt’s Institute for Social Research, where Theodore W. Adorno, modernist composer, author of Minima Moralia, and theorist of Marxian negative dialectics, was a lecturer. The occupation was the culmination of years of growing student dissent in West Germany over, among other issues, the government’s repressive new security measures and its support for the American war in Vietnam. Two years earlier, a student, Benno Ohnesorg, was shot dead by police while protesting the Shah’s visit. For a brief time, Adorno and his younger colleague, Jürgen Habermas, supported the students, speaking out against Ohnesorg’s murder. (Adorno, in a moment of unfortunate hyperbole, even claimed that “the students have taken on something of the role of the Jews.”) The romance was short-lived, however, and soon Habermas was warning of what he called “leftwing fascism” as students began interrupting Adorno’s lectures and questioning his political commitments. (A banner unfurled at one lecture read: “Berlin’s leftwing fascists greet Teddy the Classicist.”) Then, on January 31, 1969, students occupied the Institute for Social Research, and Adorno—“left no choice,” in his own words—called the cops. [2]

It is the aftermath of that phone call, at least as captured in the letters sent between Adorno and his colleague, Herbert Marcuse, that form the narrative spine of Camel Collective’s 2017 video, The Distance from Pontresina to Zermatt Is the Same As the Distance from Zermatt to Pontresina. The two-channel video shows the peregrinations of two blind men in Mexico City alongside a team of foley artists who add the sound effects to the blind men’s movements. (In filmmaking, a foley artist, or “foley,” dubs naturalistic sound effects, such as footsteps, onto a film’s soundtrack during postproduction. This is done with simple props such as empty shoes clomping on wooden boards or slabs of meat hit with hammers.) The two blind men also provide the video’s voice-over, their fingers tracing the Spanish braille translations of the Adorno-Marcuse correspondence as they speak into microphones positioned nearby the foley artists. The effect is complicated, visually and auditorily. We hear two voices in Spanish. We see the foley artists stomping on wooden planks. We watch two blind men make their way through various locations in Mexico City: busy streets, a landfill, a market. And we hear a translated correspondence between two German philosophers, long dead.

At the time of his correspondence with Adorno, Herbert Marcuse was a demigod of the American New Left. He lived in California where his post-Marxist substitution of class struggle for erotic liberation resonated with the counterculture. He also wasn’t the one—yet—whose lectures were being disrupted,[3] so his sympathy for the students could be more expansive than his colleague’s. In short, his letters sided with the students, and he admonished Adorno for not understanding their tactics. Marcuse reminded Adorno that absent “parliamentary action,” direct action was the only form of praxis left to the students. In response, Adorno insisted that student radicalism will not lead to revolution, and that their censoring violence was just another way of “inflaming” latent fascist tendencies in Germany (hence, Habermas’s “left fascism”).

Both men agreed on one thing, however: their rift was too serious to leave to letter writing, so they should meet in person. They decided on the country (Switzerland) and a season (that summer), but not the city or date. Adorno, angry at his friend’s criticisms, appeared to be playing hard to get. He would be in Zermatt that summer, and Marcuse should join him there. Marcuse reminded him that he, instead, will be in Pontresina that summer, and the distance is between the two Swiss cities was equal in both directions. The video does not say if they ever set a date. It also does not tell us that Adorno died of heart attack that summer while in Zermatt, leaving his differences with Marcuse unresolved.

The Distance is an accretion of unresolved pairings: between Marcuse and Adorno, the students and the police, the students and the philosophers, the street and the recording studio, theory and practice, the blind and the sighted, sight and sound. We are not guided to synthesize—as a good Marxist might say—any of these contradictions. How, for example, does one square foley artists with two long-dead Marxist theorists? What is one to make of the relationship between the landfill and the street? The blind men are (thankfully) not quite presented as a metaphor for the inadequacies of social theory, but nor are they necessarily the foley artist’s most adept audience. Camel Collective has stated that by filming the foley process they hoped to “demystify” the cinematic image, but foley contains its own mystification, and to watch it is to be mesmerized by a primitive sound alchemy.

The issues undergirding the Adorno-Marcuse letters also remain unresolved and retain an uncanny relevance. There are radical students censoring academic lecturers (“cancel culture!”); reflexive defenses of the police (Adorno, sounding like a centrist Democrat: “The police should not be abstractly demonized”); doubts about student radicalism as the true agent of change; false equivalencies between far left and far right (“leftwing fascism”); and even a brief mention of a poorly named pandemic (Adorno narrowly avoided the “Hong Kong Flu”). More deeply, there is the thorny problem of theory and practice, and of two men who had written the books that guided a movement, only to have that movement reject them. Much of what the New Left championed—direct action, pop culture, anticolonialism, intentional communities, free love, optimism—forms a nearly perfect inverse image of Adorno’s thought, and those concerns still drive young activists today.

The Distance aims for distancing: of subject from object, artwork from viewer. Like Brecht, Camel Collective is concerned with distantiation through staging—see, for example, their 2018 video Something Other Than What You Are, which revolves around the language and profession of theatrical lighting. Foley is for cinema, but it is also a kind of theater: playacting with rocks and oversized shoes, walking in place, making noises with one’s mouth. There is a slight line between play and work here, as there is between the real and the fictive. The blind men appear uninterested in the drama, but that only enhances the strangeness of it all. It is a studied chaos, each piece clear, in itself, but when taken as a whole, never cohering. It isn’t a neo-dadaism, confusion for the sake of confusion. And it isn’t allegory for a theory no one has read. No one element dominates, and no one position seems right. Blindness, unresolved differences, frustrations—history here is a puzzle, a puzzle whose solution is lost.

[1] Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund

[2] See Muller-Doohm, Stefan. Adorno: A Biography. Translated by Rodney L. Livingstone. Cambridge, UK: Polity Press, 2009. Livingstone and Leslie, Esther. “Introduction to Adorno/Marcuse correspondence on the German student movement.” New Left Review 233, no. 1 (1999): 118-122.

[3] That spring, Marcuse’s lecture would be interrupted by students in Rome. Their leader, Daniel Cohn-Bendit: “Herbert, tell us why the CIA pays you?”