Escape from New York

On "Escape from New York" ripoffs, forgotten film genres, bad acting, and rise of the carceral state

Hello Friends,

This week’s dispatch is an essay devoted to a forgotten1 film genre, a tiny cluster of films—three, at most—that ripped off John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981) and Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979).

In all of these films, New York is a lawless post-apocalyptic wasteland—a vision the city’s fiscal crisis and high crime rate helped promulgate. Soon, though, the genre was unworkable. The reasons for its quick decline are obvious: during the ‘80s New York pulled itself together financially, and by the late ‘90s the city was beginning a decades-long frenzy of gentrification. At the same time, US politicians, attorneys general, and private companies created a carceral state of unimaginable scale.

But the piece is not only about New York and prisons. It is also about cinematic genres, and how some genres disappear, usually because history renders them obsolete. Along the way, I discuss bad film acting, grade-Z Italian filmmaking, and how Children of Men (2006) probably ripped off its Guernica scene from one of those Italian films.

Anyway, I hope you find time to give it a look.

J

PS. If you like what you read here, please consider becoming a paid subscriber.

Escape from New York

1. The Forgotten Genre

Every so often a film genre will achieve some cultural presence, maybe even ubiquity, before evaporating from the public imagination forever. What causes this exit from the cultural scene is sometimes obvious—the end of a war, the changing of social mores—though, more usually, a genre’s departure is as puzzling as its arrival. (Think body-swapping movies of the 1980s, a genre that enjoyed blockbuster success for a few years before thankfully disappearing forever.)

The genres that do survive—fantasy epics, superhero tentpoles, romantic comedies—enjoy an aura of unwarranted inevitability. Of course space operas like the Star Wars franchise make billions of dollars, and of course high school comedies are emitted by Hollywood studios year after year. But film history could have easily gone another way: if Star Wars: A New Hope (1977) had failed at the box office, space operas might have remained the campy pastime of introverted nerds, and although high school dramas seem inescapable, cinema mostly went without them for half a century.

Every forgotten genre contains an unfinished history. A forgotten genre shows not only how different culture once was, but how different it could be. This is true for those genres that disappear full formed—like body-swapping films—as well as for those that fail to advance past a few semi-connected examples. Inchoate, slightly more than notional, these half-formed genres are difficult to locate and even harder to name. More rhetorical than actual, one must make a case for their very existence.

2. The Warriors Escape from New York

One such proto-genre nearly emerged in the early 1980s, crossbred from two (or three) films made after the nadir of New York City’s financial crisis: Walter Hill’s The Warriors (1979) and John Carpenter’s Escape from New York (1981).2 Although Hill’s film was set in the present and Carpenter’s in the near future (1997), the two present similar views of a city whose reputation had declined.

Both films are narratives driven by infiltration and escape. At the beginning of The Warriors, the titular street gang is traveling from their home in Coney Island to an inter-borough gang summit in the Bronx. The eight Brooklynites—young, earnest, macho, awkward—have never been so far from home, and against their better instincts, they arrive in the Bronx weaponless. While there, the convention’s leader is assassinated, and the Warriors are framed for the crime. The film that follows takes the form of a late-night race back to Coney Island, with the Warriors fleeing through the subway system and every gang in New York in obsessive pursuit.

Escape from New York, too, is about men infiltrating and then escaping enemy territory. By the late 1980s (the film’s future), America is overrun with crime, and Manhattan is turned into a giant outdoor prison. The prison is a heterotopia, of sorts: the island is surrounded by a containment wall, and no guards allowed on the island itself. As a robotic voice intones over the film’s opening didactic animation: “The rules are simple. Once you go in, you don’t come out.” Naturally, criminal gangs now rule Manhattan, and one day in 1997, leftwing terrorists crash Air Force One into Midtown. The President survives, thanks to an egg-shaped escape pod, but he is quickly captured by a gang leader named The Duke (Isaac Hayes) and held for ransom.

Who best to rescue the President? According to the script’s tough-guy logic, not the ineffectual military, but “Snake” Plissken (Kurt Russell), war hero and about-to-be incarcerated master criminal. Like the Clint Eastwood’s Man with No Name, from whom Russell’s laconic verbal delivery is lifted, Plissken is an asocial loner with only a passing interest in right and wrong. Expendable, nearly impervious to pain (though afraid of needles), and a little too eager to kill, the chief of police (Lee Van Cleef) judges Plissken to be the right man for the job. Plissken’s mission is to pilot himself, alone, into Manhattan and rescue the President from whoever captured him. If he brings the President back intact within twenty-four hours, Plissken will be granted immunity. If he is late, Plissken will be killed by tiny explosives injected into his bloodstream.

After exposition-heavy openings, both films let their characters loose in what feels to be unending New York nights. For the Warriors, the city is labyrinth, their escape routes blocked by burning subway stations and bat-wielding mimes dressed like Yankees. New York’s criminal class is divided into hundreds of gangs, each with their own name and elaborate costumes: the Rogues, the Orphans, the Satan Mothers, the Moonrunners, the Lizzies (the only all-women gang), not to mention the most violent gang of all, the New York Police Department.

Plissken’s New York is even worse. After losing the President’s trail, Plissken wanders the streets like a heavily armed flaneur. The city is a ruin without electricity, its streets submerged in anxious darkness. Fires burn everywhere, and when Plissken finds what is left of the President’s plane, the flaming fuselage fits right in with the scenery. Everyone seems to live underground—very literally—in caves or sewers, surfacing only for food or combat. As with The Warriors, this is a New York populated by gang members and criminals, all overseen by semi-fascist authorities. Working people and families are absent, leaving the antisocial to live rent-free in what was once prime real estate.

Much of this is in line with how America, and the world, looked askance at the city during the ’70s and ’80s. With New York in fiscal crisis and the Bronx in flames, a rubble-strewn block was as likely to represent the city on screen as the newly completed—and locally reviled—Twin Towers. Any other particularities of New York were often fudged, especially by the Californian productions on the prowl for easy-to-frame landmarks. A few New York filmmakers—Woody Allen, Martin Scorsese, et al.—were attentive to the layout, but they did it to calm their own consciences, as their 1970s audiences would rarely have dared to set foot in the city.

It is surprising, then, that The Warriors is as faithful as it is to New York geography. As we follow the Warriors from station to crumbling station, the film exhibits a nearly pedantic devotion to the intricacies of the subway system. (The subway system is probably the only aspect of New York as ruinous today that it was in the ’70s.) Instead of seeking out ridiculous and discontinuous New York set pieces, Hill worked within the city more or less as it was, even if realism required strenuous night shooting in neighborhoods hostile to carpetbagging film crews.

Carpenter’s Manhattan is shamelessly imaginary, going so far as to contrive a “69th Street Bridge” as Plissken’s only hope of escape. Even a non-New Yorker might notice that the fictional two-lane bridge—in the film, located on the Manhattan’s East Side, but shot in rural Missouri—is at least two lanes too narrow for big-city traffic. Much of Carpenter’s film was shot in St. Louis, where the production could fill whole blocks with night lighting and appropriate sci-fi wreckage. (Carpenter: “We had to look around for some city that looked destroyed…so we found the perfect location. And that was St. Louis, Missouri.”) Since the rest of the film’s interiors were shot in Los Angeles, Carpenter inadvertently created a bizarre topography oftentimes triangulating among three cities in a single scene. (After leaving a New York street, Plissken creeps through a dilapidated theater that is, depending on the angle, either the Fox Theater in St. Louis or the Wiltern Theater in Los Angeles.)

3. The Mutant Fetish

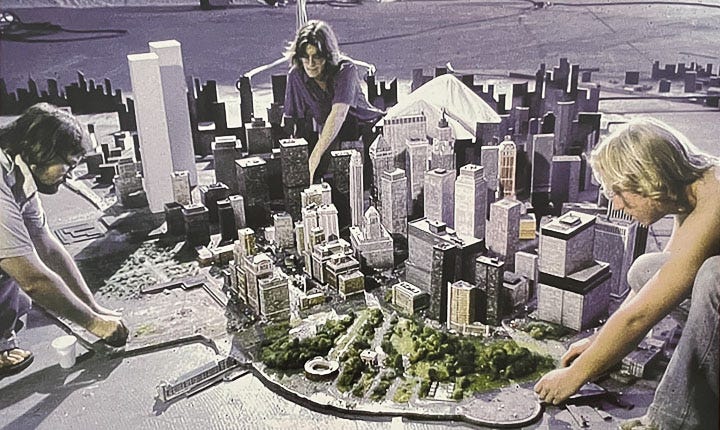

Carpenter and Hill’s films could have been edited into one, forming a single epic breakout narrative in which Plissken escorts the Warriors to safety. But despite the two films’ narrative sympathies, they do not pair into any identifiable genre. The work of making their latent connections explicit would be left to a trio of low-budget and now forgotten Italian films: Enzo G. Castellari’s 1990: The Bronx Warriors (1982) and Escape from the Bronx (1983), along with Sergio Martino’s 2019: After the Fall of New York (1983). Both Castellari and Martino were prolific genre directors, shooting Westerns, gialli, Jaws knock-offs, and, in the case of Castellari, a Dirty-Dozen-style film, Inglorious Bastards (1978), which served as the model for Quentin Tarantino’s 2006 film of a similar title.

The three films, products of Italy’s fast and dirty exploitation market, spliced their two source films into a garish new mutant genre, one that might be called the New-York-postapocalyptic-prison-escape film. Like the pile up of attributive nouns that describe them, these three films’ props, hair styles, locations, plots, and costumes are all genre dense, each signaling a different cinematic plunder. Most of the loot comes from Carpenter and Hill: there is a New York borough (the Bronx) “declared a No Man’s Land”; costumed gangs; mononymic characters like Trash and Ice and Ratchet; a missing VIP; action sequences mixing a panoply of low- and high-tech weaponry. Castellari swaps a maximum-security Manhattan for a radioactive Bronx, and instead of a kidnapped president there is the runaway daughter of a real estate tycoon.

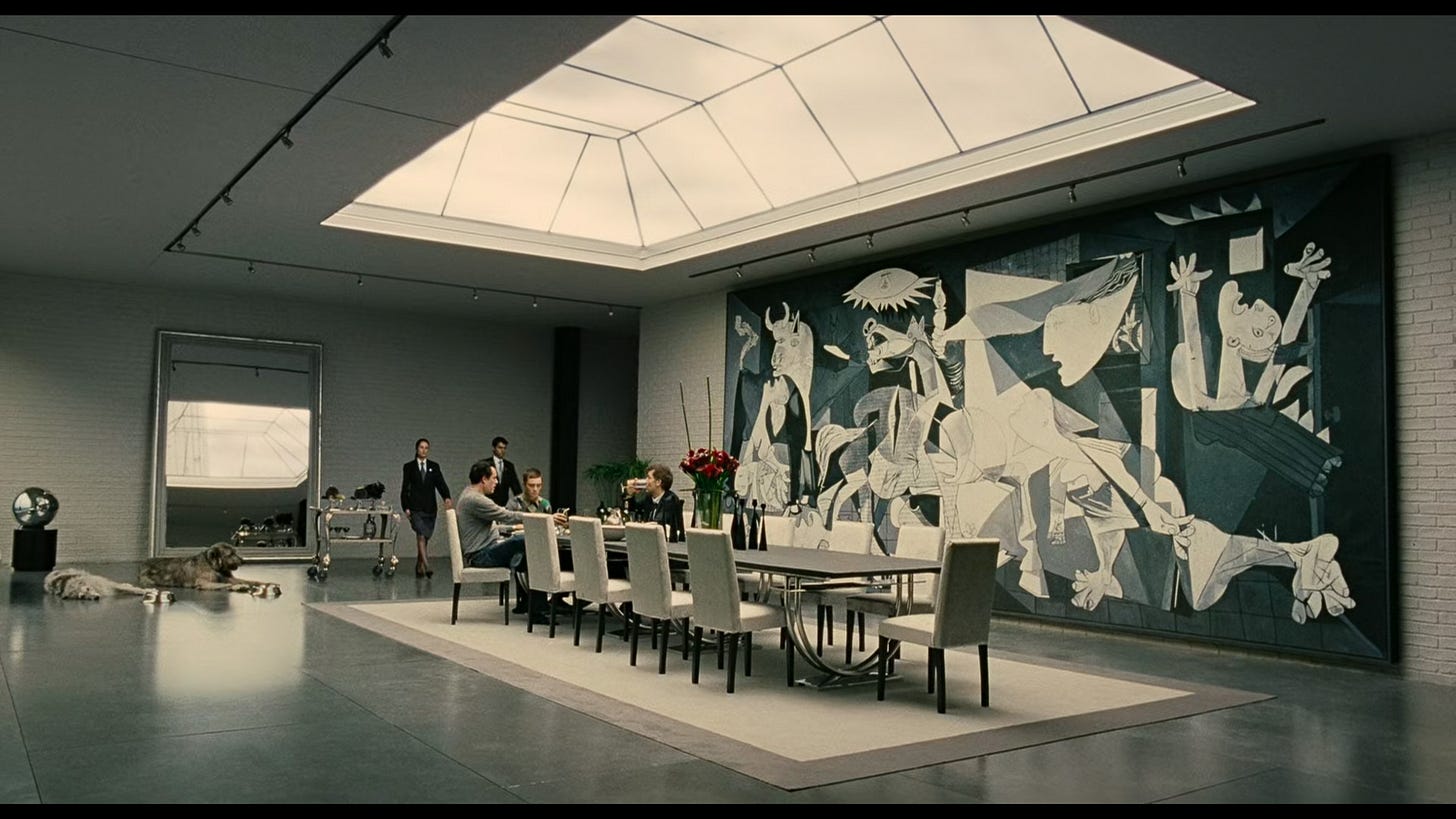

Martino’s film, After the Fall of New York, is more science fictional, going so far to include futuristic aircraft, an Alaskan ice base, lasers, and Mad Max-like demolition derbies. The film’s premise is more original than Castellari’s two films, and in a rare reversal for the exploitation market, After the Fall of New York may have been the subject of a more high-brow theft. The film’s plot is more or less the same as Children of Men (2006): a nuclear war has rendered the world sterile, but there may be one woman in New York who is able to give birth to a child. And, like Children of Men, Martino’s film also features a character who owns Picasso’s Guernica. (P.D. James’s novel, The Children of Men, does not include Guernica.)

Castellari and Martino’s films are filtered through an Italian romanticism for New York that often crosses into fetishistic exoticism. In Castellari’s two Bronx films, everyone curses with comical abandon, and the New Yawk street talk is so cartoonish even non-English audiences might hear the accent. But as with all fetishism, the fetish is only a means to a fantasy—in this case, a New York even more fictionally bizarre than Carpenter’s. Part of this high weirdness is due to budget: If Carpenter and Hill’s films were relatively cheap productions, the Italian’s are so low budget they struggled to sustain their fictional worlds. In an early scene in Escape from the Bronx, one can clearly see crew members crouching in the background, and during various action sequences in the same film, stuffed dummies do the stunt work. Unlike their cinematic templates, Castellari’s Bronx pair are daylight films. The result is apocalypse with the lights on: healthy 1980s traffic is often visible in the distance, as are very non-threatening Bronx bystanders. Sections of Castellari’s films are shot in the ruins of the South Bronx, but much of the rest is obviously shot in Italy, thus giving an even greater sense of estrangement than Carpenter’s creative geography. More puzzlingly, Castellari often substitutes locations in Brooklyn, Manhattan, Queens, and Roosevelt Island for his star borough, and in one scene, characters access the Bronx sewer system through a door located somewhere near Times Square.

Originality, fidelity to place, and realism are of no interest to directors like Castellari and Martino. Instead, they revel in the pleasure of cinematic imitation and reference. Beyond their two obvious source films, the Italians’ cinematic thievery is dizzyingly ambitious: every gesture is a pantomime, every line of dialog is an echo, every object belongs to something or someone else. The hairstyles are punk, the cars are George Miller, the gore is Lucio Fulci, the Alaskan ice station is John Sturges, the growl is Clint Eastwood, the swagger is Blaxploitation, the dubbing is awful, and everyone is in it for the thrills. This is joyful cinematic ransacking without conscience or debt—Castellari and Martino are maestros of filch. If most films pick a genre and stick with it, then these films pick a dozen and revel in their combinations.

4. The Bad Actor

Action films are often organized around a godlike male movie star, but Martino and Castellari’s New York films center their frenzies around pretty, void-like neophytes lacking both name recognition and any concern for naturalistic acting. The Bronx films feature nonprofessional first-time actor Mark Gregory (Marco De Gregorio), a lanky, long-haired, muscular seventeen-year-old the director spotted at the local gym. Gregory initially turned down the role, citing a disinterest in acting, and after watching 180 minutes of his work, it is clear Gregory meant it.3

2019 stars Michael Sopkiw, an American former sailor and model who studied acting before starring in a brief run of Z-level Euro-actioners. Less athletic and more classically handsome than Gregory, Sopkiw’s square-jawed looks are dimly approximate to that of Kurt Russell, his ur-action star.

Poorly dubbed, clad in sci-fi-primitive costumes, and surrounded by more skilled veterans of genre acting, Gregory and Sopkiw appear as oxymoronic figures: bewildered leading men. It is a problem generally suffered by the whole of low-end of action filmmaking: When your leading man does not know how to behave in front of a camera, his expected omnipotence is not only diminished, but is reversed, and instead of being the action’s prime mover, he appears as its confused victim.

It was Stallone and Schwarzenegger who made poor acting a crucial aspect of the mainstream action genre, and, over time, their star glamour served to distract from their obvious lack of acting talent. Over time, their fame transformed their congenital on-screen inelegance into a positive and even desirous trait. Their every awkward grimace, grunt, snarl, and stiff-backed turn became qualities fans imitated and then demanded to see on screen. If Stallone failed to utter his usual groan, audiences might be miffed. If Schwarzenegger did not deliver a one-liner in his Austrian-accented monotone, the film would be a failure. But smalltime action stars like Gregory and Sopkiw did not enjoy the fame that would elevate the audience’s mockery into admiration. Their hammy gestures have not been reified into world-renown pantomimes, so when their faces contort into a poor imitation of an emotion, the audience is more likely to laugh than cheer

5. The Carceral City

In all of these films, including Carpenter and Hill’s, the protagonists—and many of the supporting roles—are white. The few Black characters that do exist—the Duke played by Isaac Hayes in Escape from New York, and The Ogre played by Fred (“The Hammer”) Williamson in The Bronx Warriors—are villains and supporting characters, there solely to assist and foil the action. Like all supporting actors, Hayes and Williamson are forced to usurp every scene: Williamson, a former defensive back and a veteran of the Blaxploitation industry, is easily the the most watchable actor in The Bronx Warriors, and Hayes’s laconic presence is a perfect complement to Russel’s own snarling performance.

But despite their badass bravado, Hayes and Williamson are isolated tokens in all-white narratives, tokens that are eventually killed off in the third act. Even worse, Castellari uses a Black homeless character as comic relief, while Martino inexplicably places a Black horn player at what appears to be the only entranceway to postapocalyptic Manhattan. (The Warriors, to its credit, eventually sidelines some of its white protagonists, with the Latino and Black Warriors eventually taking center stage.)

The New York apocalypse on display is one refracted through white fears of urban decay. All of these films exclude the much more pressing fears of inhabitants of the boroughs in question—inhabitants who were and are largely Black and Latino, and who had to face the real tribulations of existing as minorities in America.

That is not to say that the films are completely clueless: By its own deranged logic, Castellari’s Escape from the Bronx did at least understand that economic displacement would govern the future of New York. But the real New York would not need men armed with flamethrowers to make way for high-rise developments. That could be accomplished by the erosion of rent stabilization laws and the creation of a system of neighborhood-by-neighborhood gentrification that engulfed the city. Crime was down and New York was on the rise, at least from a real estate perspective, and by the end of the millennium it was much more likely a neighborhood would be declared a landmark than a no man’s land.

Meanwhile, a carceral state did emerge in the United States, but it had no need to turn Manhattan into an outdoor prison. Starting at just about the time Escape from New York was released, the United States began its vast, grim project of mass incarceration, eventually locking up more people per-capita than any other country in the world. Decades of law-and-order candidates pursued policies criminalizing non-violent offenses, policies that targeted African Americans—specifically young Black men. “Three-strikes” laws and mandatory minimum sentencing condemned Black men to lengthy prison terms, terms that would guarantee later cycles of unemployment and political disenfranchisement. Yes, the future United States would be a carceral dystopia. What these films got wrong—tellingly—was who would be the future’s true victims.

Forgotten, dead, obsolete… the terminology here is inexact. I use “forgotten” mostly because the genre is no longer productive or discussed. “Forgotten” has the added benefit of suggesting cultural memory, rather than technological usefulness (“obsolete”) or the lifecycle of an organism (“dead”).

A third film, George Miller’s Mad Max 2 (1981) also played a role, though it mostly generated its own bizarre, vehicular subgenre.

After the Bronx films, De Gregorio went on to lead a few more Italian exploitation films, including the Native-American-themed Rambo knock-offs Thunder (1983), Thunder II (1985), and Thunder III (1988). He then vanished from public view, evading fans and former collaborators alike. After several attempts by fans to find De Gregorio, two Italian film writers recently discovered that the former actor tragically committed suicide in 2013.