The Diaries of Raúl Ruiz

On the diaries of the Chilean filmmaker as translated by Jaime Grijalba Gomez

For the past five years, Chilean filmmaker and writer Jaime Grijalba Gomez has been translating the diaries of his late compatriot, the bizarre, brilliant, and supernaturally prodigious Raúl “Raoul” Ruiz (1941-2011). Ruiz was exiled to Paris after the 1973 coup, where he continued a career that included directing more than 100 films, original television shows, plays, and operas, as well as writing several books of cinema theory. (There were also poems, art installations, and at least one novel.) Unfailingly inventive, scholarly, and surreal, Ruiz oftentimes had little interest in whether his audiences could follow his peripatetic narratives. The resulting filmography is uneven terrain, for sure. Like Jess Franco or Takashi Miike, Ruiz operated in that uninhibited zone that only the ultra-prolific enjoy.

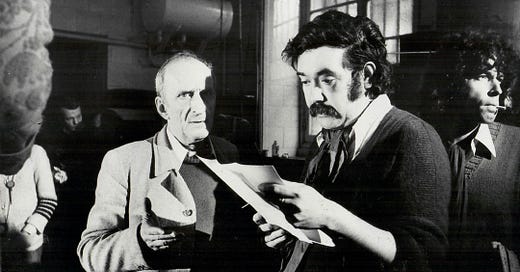

An heir to both Jean Cocteau and Roger Corman, Ruiz’s work existed primarily in the European arthouse. His early period in France begins in the 1970s with micro-budgeted experimental shorts and features, financed mostly by France’s INA (Institut national de l’audiovisuel). Unlike his fellow exiles, Ruiz turned his back on radical politics, instead engaging himself with the legacies of the European avant-garde. He worked almost exclusively in fiction, making only a few documentaries, most of those being parodies of the form.

His best-known film from this early period, The Hypothesis of a Stolen Painting (1978), is exactly this kind of parody. A black-and-white TV adaptation of Pierre Klossowski’s novel, The Baphomet, Hypothesis is also a tricky art mockumentary, complete with a soporific emcee who speculates on arcane art history. The story that unfolds is a predecessor of Umberto Eco’s Foucault’s Pendulum along with many of the postmodern conspiracy narratives of the coming decades. Dense, highly referential, alternatively confusing, boring, and brilliant, Hypothesis a fairly typical film for Ruiz. It also happens to be among his best.

By the late eighties, all of the Ruizean narrative elements were on the table: amnesiacs, pirates, detectives, expressionist lighting, Dutch angles, lurching plots, artificial dialogue, self-reflective staging, narrative mise en abymes. In true Corman style some of the films were shot in mere days, oftentimes losing funds midway through filming. Wim Wenders’s The State of Things (1980) is partially about Ruiz’s struggle to film The Territory (1981), a cannibal movie that ran out of film stock before being rescued by Wenders’s own 35mm stash. Wenders then poached Ruiz’s crew and cast to make his film, much to Ruiz’s chagrin. (I may write about these twinned productions for a future newsletter.) At the end of the ’80s, Ruiz came to New York to shoot The Golden Boat (1990), and everyone from Jim Jarmusch to Kathy Aker and Annie Sprinkle showed up. That’s how things went for two decades: no-budget production after no-budget production, with some film festival success, waxing and waning critical support, and an international audience of a few hundred insiders.

Then, in the mid-nineties, Ruiz started working regularly with the legendary producer Paulo Branco. Zero-budget quickies gave way to international co-productions featuring superstars such as Catherine Deneuve and Marcello Mastroianni. Melvil Poupaud and John Malkovich were regulars, with Malkovich at one point declaring Ruiz his favorite filmmaker. The films from the late nineties and aughts managed to be just as intellectually dense as the early work but with wider distribution and mainstream critical awareness. They were just as uneven, too. To give one example, in the span of two years (1998-99) Ruiz released a perfect adaptation of Proust’s Time Regained (1999) starring Deneuve and Malkovich, preceded by the unwatchable Shattered Image (1998) starring Bulle Ogier and William Baldwin.1 Ruiz kept releasing at least a film a year, on average, until his untimely death in 2011 at 70 years old.

Among all that frenzy, Ruiz found time to keep a diary. He started in 1993 at the age of 52 and continued until the end of his life. The entries are fascinating, though their subject is often elusive. Surprisingly for such a workaholic, Ruiz has little to say about the nuts and bolts of filmmaking. He theorizes often, but rarely writes in much detail about any one production.

Instead, the diaries focus on what I always assumed was Ruiz’s non-existent downtime. There is a lot of talk of food, wine, cigars, books, naps, flights, hotel rooms, philosophy, lunch meetings with famous and semi-famous people, and—did I mention?— food. The food passages—feasts eaten, cooked, enjoyed, regretted—are overwhelming. (After a dinner he hosts, for example, Ruiz brings everyone out to a nearby Belleville Chinese restaurant for a second dinner washed down with yet more bottles of wine.) Ruiz is very open about his health issues, too, and one begins to worry that maybe he should cut back a little. Diabetes inevitably enters the picture, along with gout and kidney troubles. The feasts, however, continue.

Ruiz’s gastronomic appetites are only rivaled his intellectual pursuits: in one 24-hour period Ruiz might read Mysticism and Logic by Bertrand Russell, Anthology of Black Humor by André Breton, and some Théophile Gautier. Most weeks find him burning his director’s fees in Parisian antiquarian bookstores where he stalks expensive first editions. There are also meetings with Salman Rushdie; film festivals; lonely lunches at a neighborhood Japanese restaurant; dinners with his wife, the filmmaker Valéria Sarmiento; lots of unproduced film scripts; lots of produced film scripts; Johnny Hallyday; and trips home to see his mother. “The Robbe-Grillets” make semi-regular appearances, and at one dinner party Ruiz discusses his diary with them:

“We talked about the reason for writing an intimate diary when it is quite possible that it will be published, which forces one to improve the style and say things destined to a third party (that’s not my case). I told them (but no one was listening to anyone) that, in my case, a diary is used as an aide-mémoire, but above all, because it gives to everyday life the character of a journey, of a voyage. Wandering, the natural way in which life presents itself, takes on the meaning of an investigation, or a quest.”

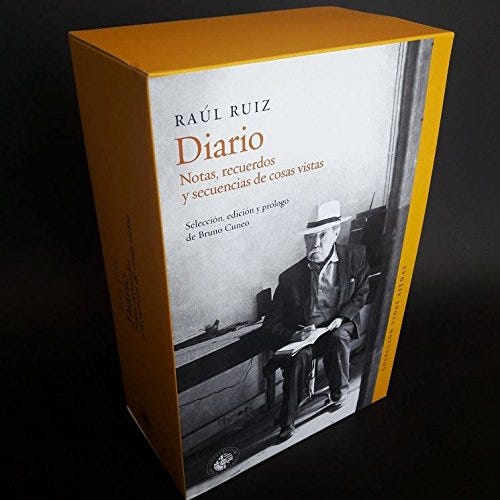

Ruiz wrote the original diaries in Spanish, and they were published in two large volumes by the Chilean publishing house Ediciones UDP in 2017. The following year, Grijalba began his translation project. Since then he has been sending out one diary entry per email, several emails per week, sometimes more than one per day. Each entry is preceded with a brief introduction by Grijalba, along with frequent (and unnecessary) apologies for days skipped due to busyness, illness, etc. The project has reached, as of this writing, the entries of 2003. Again, it is an “unofficial” translation and a labor of love, so if you subscribe make sure to send a donation Grijalba’s way.

Last year, the publisher Dis Voir also translated a slim selection of diary entries into English. It’s a welcome contribution to the library of English-language Ruiz literature, but the abridgment gives little sense of the diary’s scope and often produces unnecessary confusion. Ruiz can elide important personal information, and the Dis Voir book makes it difficult to tell whether omissions are the choice of the author or editor. Ruiz’s late-life liver transplant, for example, is only alluded to in a single sentence explained by an editor’s footnote.

I’ve been receiving Grijalba’s emails for several years now, and reading them has become a small part of my weekly routine. The emails give one the sense of living a parallel life, a quality Ruiz plays with when his diary splits into two parallel narratives, one fictional and one real. (Or that is the conceit, as I understand it, since there is no way to fact check what is happening.) The complication is unwarranted, but it is also pure Ruiz. (The diary eventually realigns with reality.) Split or not, the project—Ruiz’s, but also Grijalb’s—is scaled perfectly to its subject: epic and overstuffed with the pleasures of creation. Sign up on TinyLetter before it’s over.

Postscript: Ruiz’s gargantuan filmography is daunting, but if you are interested, start with Time Regained. The film is Ruiz’s most accessible. If you hate it, stop there. It stars Marcello Mazzarella as Marcel, Catherine Deneuve as Odette, plus a top-form Malkovich as the Baron de Charlus. If you love it, try his Malkovich-led Klimt biopic, Klimt (2006), which is more-or-less the same as Time Regained in tone and form. (There is a longer director’s cut of Klimt worth tracking down.) Then try his TV series, Mysteries of Lisbon (2010). Some say the series is his best work, though it isn’t my favorite.

Unless you live in France, you will probably need to turn to eBay, YouTube, BitTorrent, and various semi-legal download sites for the next films. (Thought there are a few regionless DVDs out there.) Ruiz was a rare master of the short form: seek out the aforementioned The Hypothesis of the Stolen Painting (1978) and Colloque de chiens (1977) for two of his best. (Though, at 66 minutes, Hypothesis is probably considered a short feature.) Finally, after Genealogies of a Crime (1997), The Territory (1981), and City of Pirates (1983), you will be a true Ruizean.

To be fair, Shattered Image has its supporters.