Hello friends,

What follows is the first in an occasional series of posts related to a new film and works on paper I’m developing about the planet Mars. The project looks at Mars in cinema, Mars as a setting for fiction, Mars as a subject of scientific photography, and Mars as a colonial fantasy. It’s an expansive research project, so this newsletter seems like an appropriate place to put the detritus that may or may not appear in the final works. I hope you like it.

See you here again soon,

J

The Mars Project: On Aelita: Queen of Mars, Aleksandra Ekster, and Martian Communists

For much of the 19th and early 20th centuries, Mars was a fantasy—oftentimes a utopian fantasy—rarely resembling the (mostly) dead rock we know it is today. Mediums claimed our dead lived on Mars. While under trance, a feminist Spiritualist wrote a utopian novel set on the Red Planet in which women ruled and men did all the housework. Mars was a place populated by alien royalty and ancient civilizations. Some scientists also unwittingly contributed to this fictionalization by falsely believing the planet was crisscrossed with “canals.” (More on these canals in a later post.) Starting with the first Martian orbiters in the 1960s, the planet became a site exclusively for materialist, scientific experimentation. This disenchantment of the real Red Planet changed fictional Mars, as well. If we are to believe that Matt Damon’s character in The Martian (2015) can survive on Mars alone, it is because his character is a resourceful botanist. (“I’m going to have to science the shit out of this,” he says of his dire situation.) No adult contemporary story would have him instead be rescued by, say, a Martian Queen.

This wasn’t always true. One of the more bizarre films set on Mars involves just such a queen (a princess, in fact): the 1924 Soviet silent film Aelita, a.k.a. Aelita: Queen of Mars. I first came across Aelita last year while visiting the Centre Pompidou’s Women in Abstraction exhibition, a sprawling survey of more than one-hundred 19th- and 20th-century female abstract artists. The exhibition held a lot of discoveries for me, but the standout was a wall or two devoted to Aleksandra Ekster (1882-1949): Russian Modernist painter, theatrical set designer, and movie costumer, who lived, among other places, in Kyiv, Odessa, Moscow, and Paris.

On view in the museum was a short, grainy excerpt from Aelita, plus various examples of Ekster’s costume designs. Aelita was Russia’s most expensive film production and one of the earliest sci-fi feature films. The film was based on a 1922 novel by the Russian poet and author, Aleksey Nikolayevich Tolstoy (Leo’s distant relation). Much of Tolstoy’s novel cribs Edgar Rice Burroughs’s successful Barsoom series—a cycle of novels also about a human (John Carter) who travels to Mars and becomes romantically entangled with local royalty. The protagonist in Tolstoy’s novel is a Soviet engineer named Los who is building a space rocket in a shed. (When asked how he’s funding his one-person space agency, he laconically responds, “the republic.”) Los is tragically lonely: mourning a dead wife, he also can’t seem to find anyone to leave Earth with him. At the last minute, a bored ex-cavalryman signs up and the two take off for Mars, where they find the famous Martian canals and a planet at war with itself. The planet is populated by lost Atlanteans—a detail owing something to Helena Blavatsky’s weird racial theories—as well as multiple other “lost races” that have been doing battle with one another. (The racialization of alien life in Aelita is confusing and a typical example of the era’s white colonial imagination.) There is much derring-do, an interplanetary love affair, and giant spiders, culminating in a red Marxist-Martian uprising.

Little of which, unfortunately, makes it into the film. Made during Lenin’s New Economic Policy (NEP), the production of Aelita benefited from nearly unlimited funds at a time when much of the country was still poverty-stricken. The studio Mezhrabpom-Rus wooed director Yakov Protazanov out of his self-imposed European exile, promising him worldwide distribution and a lavish budget—both of which the studio delivered. The film he made in exchange is a Marxist bait-and-switch: What on the poster might be billed as interplanetary adventure, instead turns out to be a depressing two-hour Soviet melodrama set mostly on Earth. Except for brief scenes at the film’s start, the novel’s Martian material was compressed into the film’s last half-hour, having been replaced with a grim story of destitute Muscovites struggling during the NEP. (Come for the Queen of Mars; stay for the lessons in state-managed economy.) The mostly depressing story is punctuated with moments of humor, much of which hasn’t aged very well.1 There is a great gag, however, in which the queen, with the help of a remote viewing device, observes humans kissing. She then tries it out on another alien. Hijinks follow.

If Aelita is sometimes charming, it is mostly because of Ekster’s costumes and Isaac Rabinovich and Victor Simov’s brilliant sets. (Yuliya Solntseva’s performance as Aelita is a major contribution, as well.) Ekster was born to a wealthy Belarusian-Greek family in what is present-day Poland. She grew up in Kyiv, where she also studied art, and later presided over the city’s preeminent salon. Ekster then moved to Paris, became a cubist, participated in the 1914 Salon des Indépendants and other exhibitions, and moved among Paris’s avant-garde. Her work eventually became non-objective, and she moved back to Russia where she began working as a set and fashion designer.

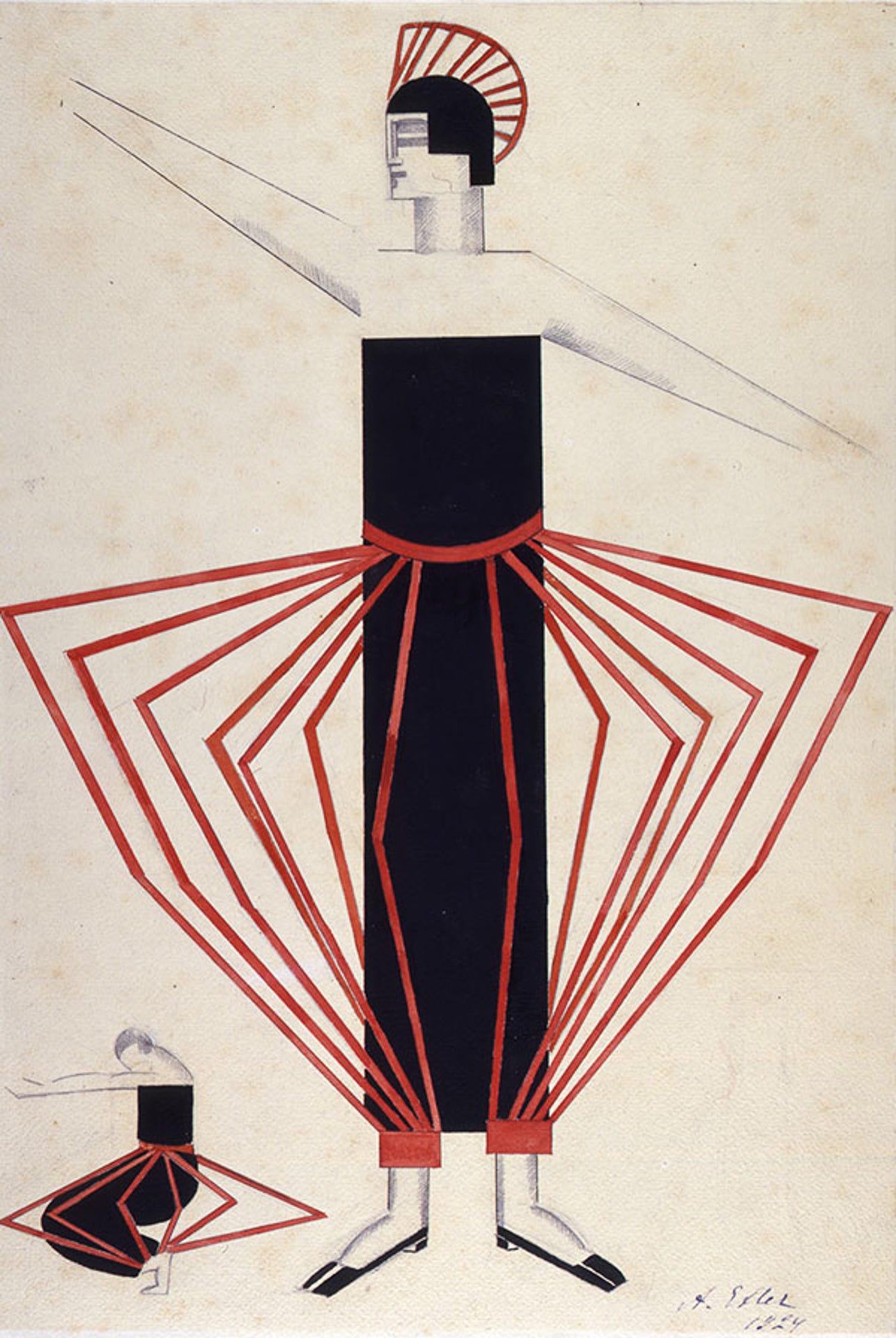

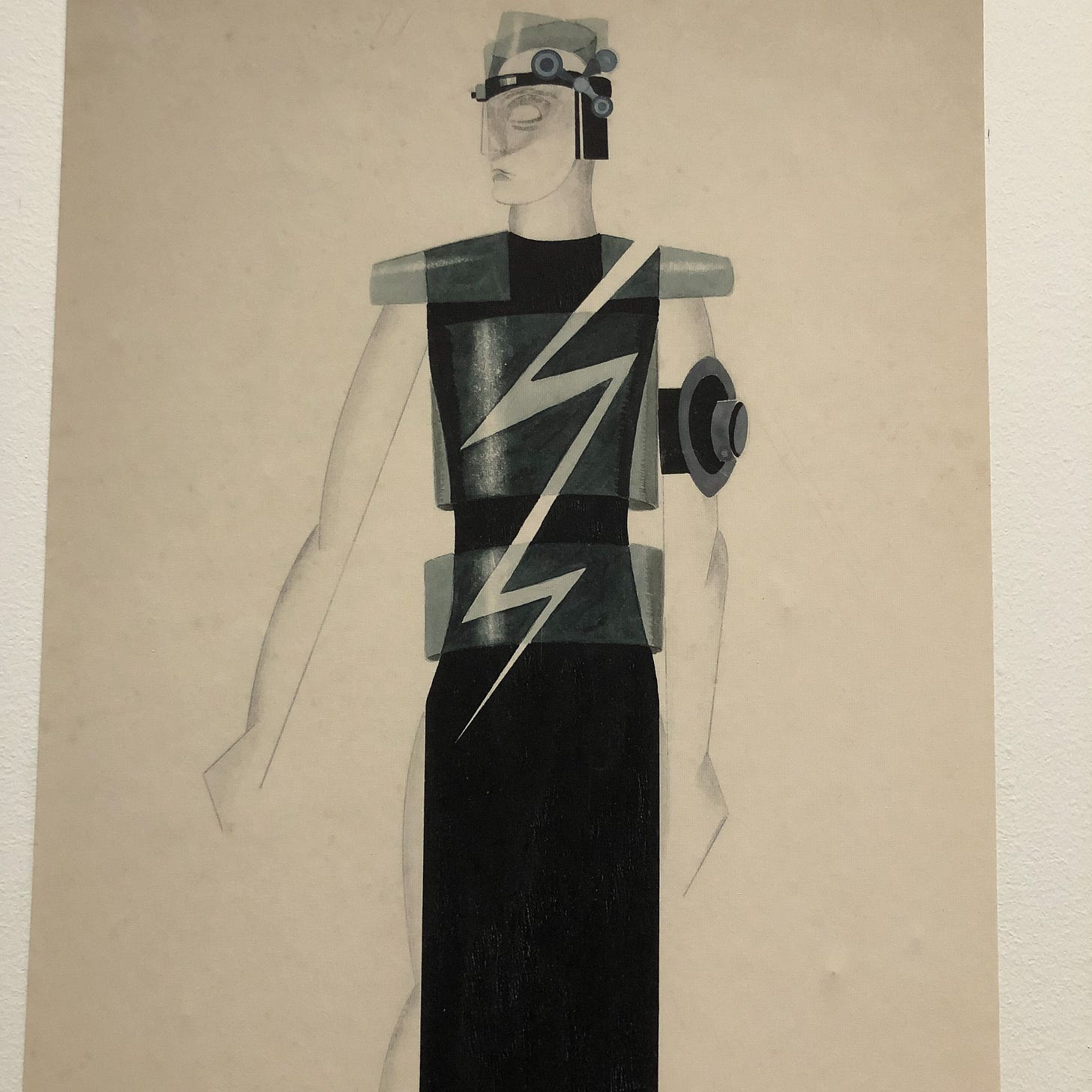

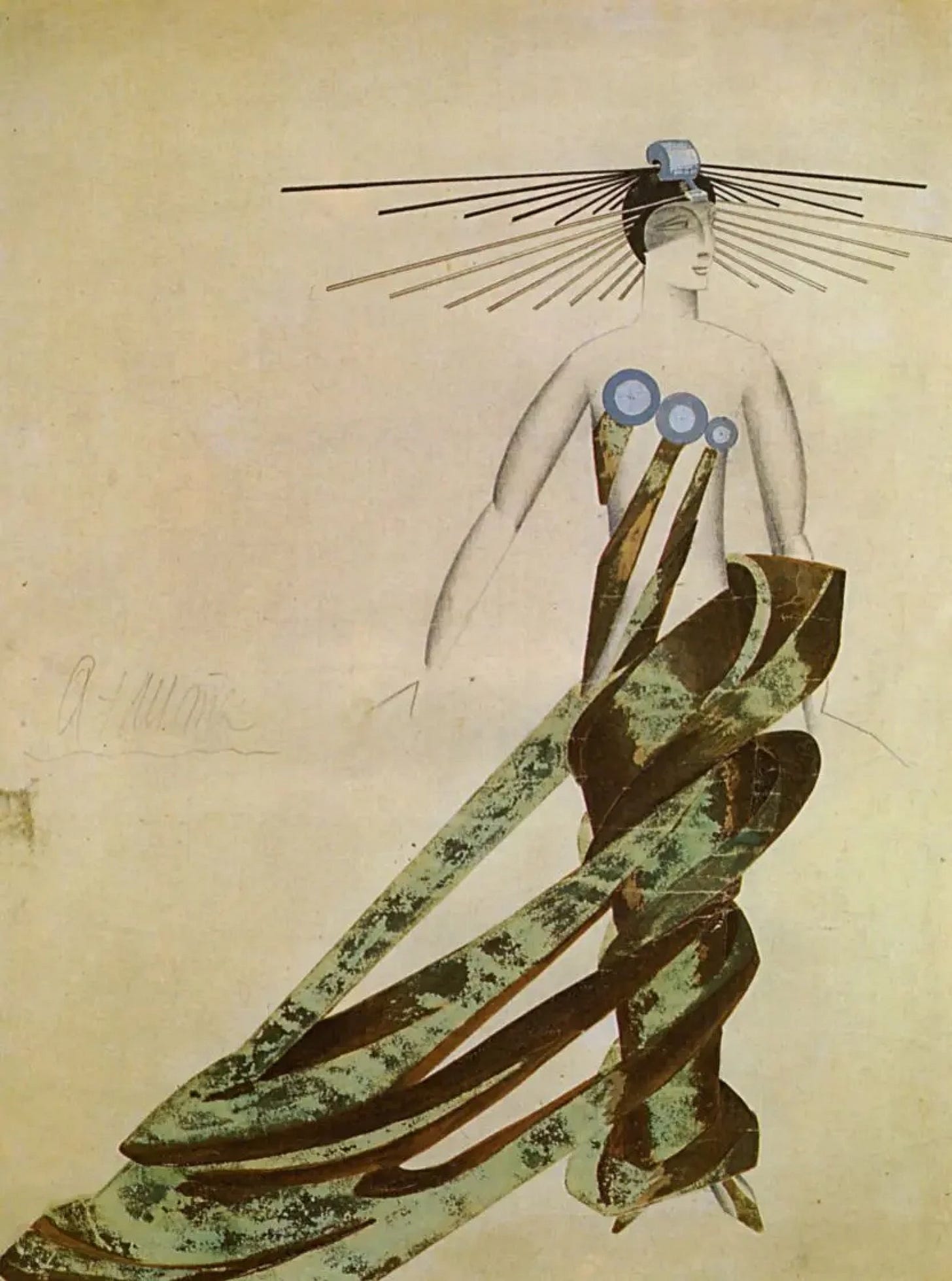

Ekster’s work for Aelita is Modernist, dynamic, layered in cutting-edge plastics and angular geometries. Despite being unable to use color, her costumes are a visual delight, especially after ninety minutes of characters dressed in moth-eaten wools. One character’s dress sports a kind of light, foldable chassis that expands whenever she bends her knees. There are cyborg body armor designs with forearm-mounted lasers that look like proto-Storm Troopers. The bizarrely monobrowed Aelita wears multiple shimmering dresses and complex, radiating crowns. It is all very alien and very modern—in Aelita, the two might be the same thing. Latter film designers agreed: Ekster’s costumes most likely created the future-style for a whole generation of sci-fi films, including Metropolis (1927). (A fashion historian might have more to say on Ekster’s relation to Pierre Cardin, as well.)

Aelita ended up being a paradoxical creature. It was an expensive film about poor people, while being a Marxist export about very local problems. It was a science fiction film about a man who gives up his fantasies of space travel, while being a film that set some of the standard for those fantasies. Trying to be both Marxist propaganda and capitalist entertainment, the film was popular with the Russian public, but Russian critics attacked it. Protazanov survived, and enjoyed a career under Stalin. Tolstoy, too, went on to prosper under the regime. The year Aelita was released, Ekster left the Soviet Union for Paris, where she continued her work until her death in 1949. Aelita, meanwhile, was buried. Unlike most films of the period, it somehow survived.

That you for reading this week’s newsletter. If you liked what you read here, please consider becoming a paid customer by clicking the button below.

PS. I realize that the clips of Aelita I’ve included above are hopelessly low resolution (less than SD, in fact). Apparently The National Film and Sound Archive of Australia has made a 4K restoration of the film recently. The NSFA’s work looks stunning:

In his classic Kino: A History of the Russian and Soviet Film, Jay Leyda gets sniffy about Aelita, going so far as to dismiss the “over-vaunted” sets and costumes. Instead he praises the film’s comedic bits—scenes that are, in hindsight, so forehead-slapping bad, they make me doubt not only Leyda’s critical acumen, but his basic sanity.