Hello,

This week I am sending out an excerpt from “The Narco-Image,” a new essay published by Do Not Research.1 The piece is about how addiction has become a new model for image consumption. Today's viewers are no longer only voyeurs; they are also addicts whose drug of choice is the image. “The Narco-Image” has been a long time in the making, and I’m happy DNR’s editor, Joshua Citarella, chose to publish it. The essay’s topics include: video game, internet, and porn addictions; compulsion loops; 12-step programs for images; the films of John Carpenter; cinema as software; Linda Williams’s frenzy of the visible; and bliss points. It is a long piece; only the first part is included below. The rest can be read on DNR’s website.

Best,

J

THE NARCO-IMAGE

“Binge responsibly”

- Netflix advertising slogan

Until recently media viewers were voyeurs, peeping at televisions and movie screens from a safe distance, their gaze conceptualized as a psychosexual form of mastery. But voyeurism as a model is no longer adequate to understand how viewers consume media. Viewership is no longer distant and controlling. Rather, the contemporary viewer is an addict, and their drug of choice is the image. The mode of desire for the addict-viewer is more: more films, more TV, more clicks, more downloads, more levels, more seasons, more episodes. Unlike scopophilic sadists, today’s viewer-addicts give up control, perhaps even lose control, helplessly spending long nights bent over laptops and tablets, clicking “watch next episode” until dawn. Images are no longer scarce, and the moreish addict-viewer is, in part, a product of this post-scarcity image economy. There is always another season to watch, another show to get into, another streaming service to sign up for, and the viewer is potentially immobilized before all of the choices. (Netflix calls this problem of too much choice “decision fatigue.”) For viewer-addicts, scopophilia has become scopomania, with extreme viewing habits comparable to binging on food or narcotics. (The word “binging” itself, when referring to watching television shows for long periods of time, was borrowed from addiction lingo, replacing the more athletic “marathoning.”)

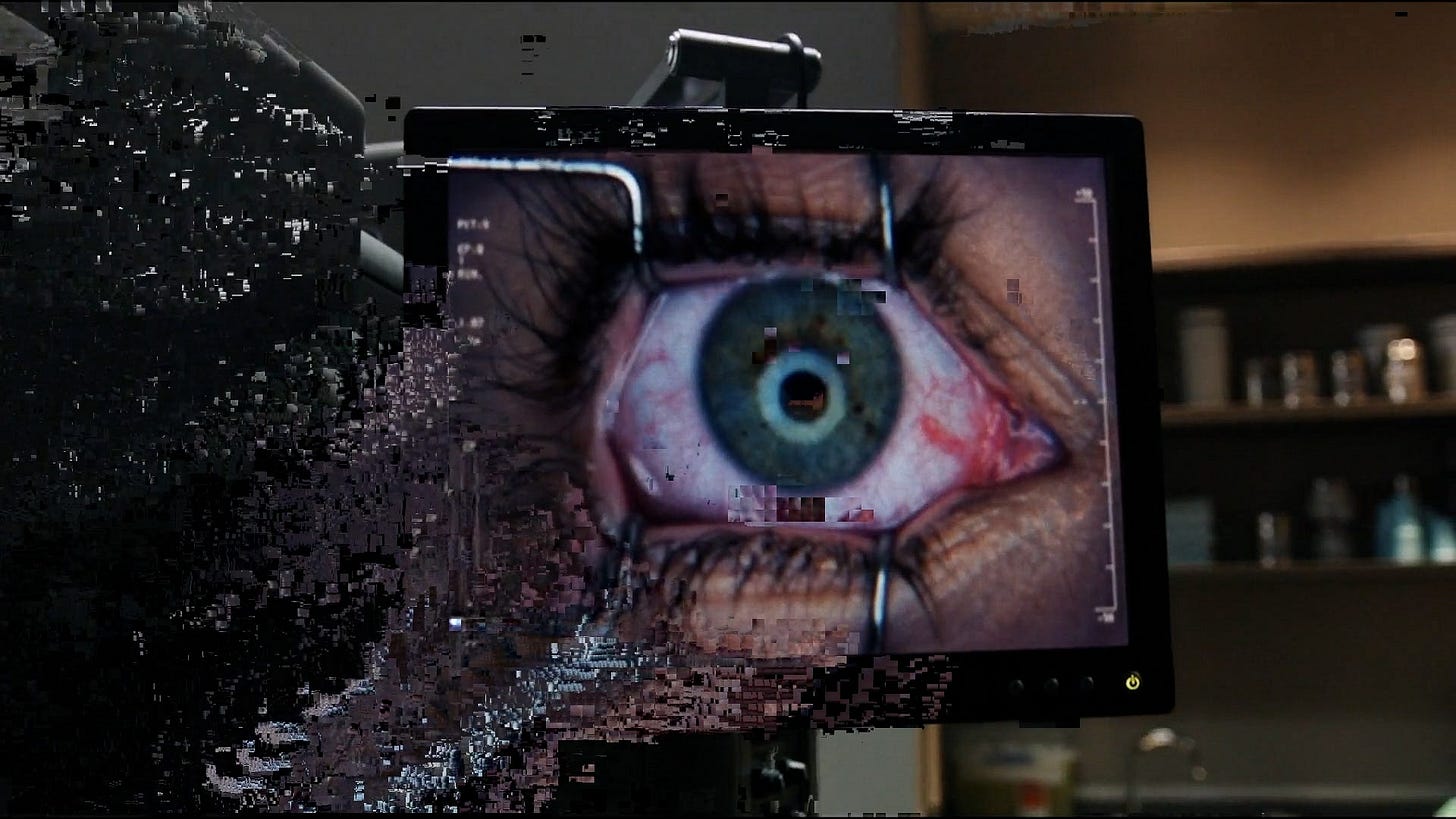

Meanwhile, images are sold, studied, consumed, abused, discussed, distributed, and fretted about as narcotics would be. This new, narcotic image—a “narco-image”—produces dependency, and sometimes requires detoxification and rehab. In response to this narcotic image, there are Porn Addicts Anonymous, Computer Gaming Addicts Anonymous, Internet and Technology Addicts Anonymous, Media Addicts Anonymous. (“We admitted we were powerless over media—that our lives had become unmanageable.”) In the same way that an addict may have to consume larger quantities of a drug in order to experience the same effect, narco-images deliver harder sex scenes, more explicit gore, and more violent action sequences. These narco-images cater to desensitized audiences, whose idea of a good time is watching two hours of simulated torture. The narco-image is loud, big, explicit, close-up, repulsive, violent, high-def, scary, thrilling, pornographic, taboo, muscular, slick, rendered, high-end. Like any successful drug, the narco-image delivers the goods, but rarely satisfies, always leaving room for an even bigger high somewhere down the line.

A small-scale publishing industry now devotes itself to the travails of lives ruined by Internet, phone, and porn addictions. Most of these books focus on attention, its loss and its fragmentation. Paradoxically, though, viewer-addicts suffer from an overfocusing of attention: i.e., the monopolization of attention by specific image regimes. A viewer-addict may not be able to finish a book or pay attention at school, but that same viewer can regularly spend hours gaming or watching the latest season of a television show. One can read of viewer-addicts ignoring their families for e-sports and compulsively watching porn at work. One can read of careers and marriages lost to video game binges, of innocent TV fans landing in media detoxes and cleanses, stories that usually end in self-discovery and twelve-step enlightenment. One can even read of harsh prison camps that beat screen-addicted teenagers into catatonic sobriety. The stories are sensational, verging on moral panic. But one thing is clear: our relationship to the image has changed, and what is feared is not only what people are watching, but how much and how often, and with what degree of self-control.

Addicts, at one time visible only in social problem films (Man with the Golden Arm, 1955; Panic in Needle Park, 1971), have proliferated throughout television and film. Boozehounds, pill poppers, cokeheads, crackheads, tweakers, stoners… all sorts of addicts have come to populate every television and cinematic drama, usually in starring roles. Just as the schizoid hero may enact late capitalist anxieties about the nature of reality (Fight Club, 1999; Mr. Robot, 2015-19), the protagonist-addict embodies the compulsiveness of contemporary viewership. Viewer-addicts can watch protagonist-addicts gamble away their paychecks, get high in shooting galleries, show up drunk to work, relapse and recover, make amends, and break promises. Almost every television show includes one protagonist-addict, and some (Mad Men, 2007-2015; Euphoria, 2019-; etc.) feature whole crowds. Television narrative has changed accordingly, supplementing the usual three-part arc with the up-and-down rollercoaster ride typical of the addicted life. Since, as recovery programs teach, addicts are addicts even when they aren’t using, recidivism will forever be a threat for the protagonist-addict. The struggle of addiction is therefore narratively endless. Against the closure of psychoanalysis is the interminable burden of the protagonist always in recovery. The new hero cycles in and out of rehab, enjoying huge narrative upswings before collapsing in despair.

Continue reading on Do Not Research.

For those of you who don’t know Do Not Research, it “is a platform for writing, visual art, internet culture research and beyond.” Be sure to subscribe.